Showing posts with label ICT in Conflict & Disaster Response. Show all posts

Showing posts with label ICT in Conflict & Disaster Response. Show all posts

ICT in Conflict & Disaster Response

Christine Broenner (MSc. Geography), a freelance consultant, advises on the design and use of geographic information systems (GIS) and on information management in support of decision-making in spatial development contexts. She works on issues of collaboration, information sharing and inter-agency coordination and is interested in the role ICT can play in complex, dynamic and unpredictable emergency management and crisis situations. You can contact Christine at info@whenmapsmatter.com Laura Morris is an independent researcher in crisis communication. She is currently writing up research on the ways in which people and organisations are affected by limitations in communications in political crisis situations and the ways in which these limitations can be bypassed. The research has special reference to the recent crisis in Libya and the MENA region generally. Click for more information about this project. She is also freelance writer for HaitiRewired. Laura holds a Masters in Social Anthropology of Development from the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. You can contact Laura at communicationcrisis@live.co.uk In recent years we have transformed the way we prepare, respond to and manage disaster and conflict globally, through the rapid uptake of new technologies, the increasing use of the internet for two way communication, the prevalence of social media and the ubiquity of mobile telephony globally.

Transforming Technology in Disasters

But what has also been transforming is our understanding of the importance of timely information for creating more effective outcomes in emergency situations. How we view information has changed and the sources of emergency information has also changed. Where as once it was thought that victims of crisis were merely that – victims, it is now understood that victims can simultaneously be responders, bringing aid to themselves, as well as journalist, providing real-time reports for the benefit of the whole affected community. We have seen this famously in the aftermath of the devastating 2010 Haiti earthquake where affected people actively engaged in rescue efforts by means of purposefully using their mobile phones to coordinate and organise help, and most recently in the Arab uprisings where protesters wielding camera phones have documented human rights atrocities and state violence on Youtube and other social media outlets, via clandestine satcoms, in the face of severe media and communications censorship. Syrians are the current victims of kill-switch censorship at the hands of the state regime.Speak2Tweet, which uses fixed line telephony and audio texts for sending tweets, is an interesting example of how 'new' and 'old' technologies can work together through this kind of censorship. Disaster management agencies can no longer view disaster affected communities as mere dependents (for this was never the case) now that so many are equipped with the communication tools to get what they need where they need it and to make those providing relief more accountable for what they do. International agencies likeOCHA and the Red Cross, as well as nationally based disaster management agencies, arebeginning to consider how community based information can be effectively gathered and used to support response efforts. However, it is not only the people affected by disaster themselves that make use of the ever new technical possibilities to communicate and contribute information in emergency situations, it is also those members of the so called'crowd', anyone networked to global communications, who want to help or have relevant knowledge that can be used by emergency response authorities. It is worth mentioning the fact that the possibilities which tech tools offer are changing continuously. This poses challenges to those working in institutionalised ways leaving little room for flexibility. Taking on board these new tools, and more so, an unpredictable new source of information, the crowd, can be a daunting prospect, but also offers a huge potential of opportunities. Many efforts of establishing how to engage with and work in concert with others assisted by tech tools are underway. Australia for example has some remarkable initiatives that are focusing on the use of social media for information gathering and dissemination during emergencies, and for enhancing the disaster resilience of their communities. One of them is the AlertSAwebsite, that aims at providing South Australians with an all-hazards emergency warning and information system in an online information platform. Management agencies using GIS and satellite and aerial imagery and aided by community-based and crowdsourced support can more easily target their efforts where it is most needed. Crowdsourced geotagging of images can be an efficient way of managing large amounts of image-based information. In the aftermath of the very recent Hurricane Sandy, FEMA coordinated with crowdsourced volunteers to tag hundreds of aerial images indicating the severity of the damage done to the properties within the pictures in order to prioritize need for the worst affected areas. Technologies can now undeniably play a crucial role not only in emergency response coordination efforts, but in mitigation and post-crisis management efforts too. And these efforts are as deep as they are wide, as are the efforts to understand the role of ICTs in emergency and to learn from and to make use of good practices in the field of ICT in emergency. The number of tech tools that have been developed seems overwhelming at times, so picking out the ones that help coordinate relief and recovery effectively may not always be a straightforward task.Why an ICT4D Crowdmap?

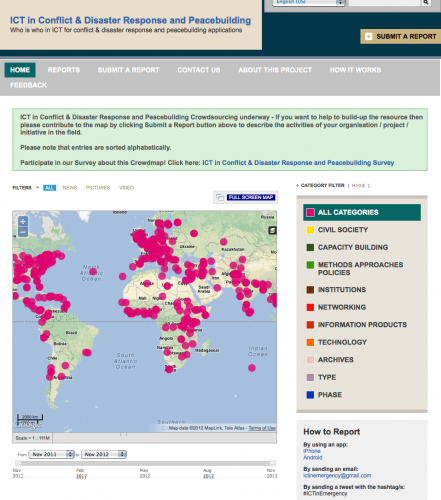

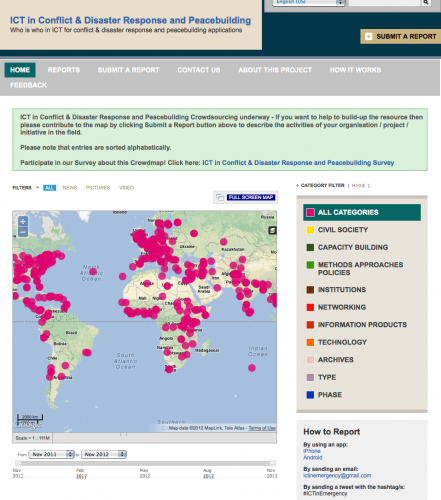

A year ago whilst delving more deeply into the subject matter, we considered how we might use one of these 'tech tools' to capture the big picture of who was doing exactly what in using ICTs in emergency. The platform we chose, is amongst the more famous of tech tools for emergency: Ushahidi"s Crowdmap.

Not only could it provide the perfect platform for visualising the global picture of this field, it also allowed us to categorize projects, programmes and initiatives in such a way as to render the information much more useful than it would have been as a static map. But what was even more interesting was the idea that because it was a Crowdmap the information on it did not need to be limited to what was known to us alone; instead, it was open to anyone who had relevant information to offer – through simply submitting a report to us. Managing the knowledge of the subject matter was to be an experience for the crowd; a very exciting prospect when considering creating a global project with limited resources. What we hoped from the ICT in Conflict & Disaster Response and Peacebuilding Crowdmap was to create a space where those within the field could discover new and relevant tools, where they could work with others to share information and where they could learn what works as good and relevant practice in the field of ICT in emergency.

Source: https://www.ushahidi.com/blog/2012/12/20/going-digital-emergency-management-in-the-21st-century-the-ict-in-conflict-disaster-response-and-peacebuilding-crowdmap

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Recent Blog Posts

000-search-keywords-terms-associated-to-child-pornography

10 things to do for stress management

9 Tips How to Read Her Sexual Language

A road towards re-silience

Activities which helps reflections in Training

AD

Ad CPM Networks

ad network

Ad Networks

ad-network

ad-networks

Adbooth

Adbooth Adnetwork

adcash

adnet

Adnetwork

adnetworks

ads

Ads for cash

Adserver

Adversal

advertising

animals

Apple Cake

Apple Cake recipe

Aptis Test Sample Voice recording

Aptis test sample preperations

Attendance rate in percent

Autosurf

Autosurfs

basic seo

basics of blogging search engine optimization.

best ads

Best Low Payout

Bhutan

Body Language

book review

Book Review Defending Jacob

Book Review Orphan Train

boost

boost traffic

Bounce Rate

Bubble News

Build Effective Social Skills

Building a Policy

By Anohar John

Career Planning

CashInLink

Catering Equipment

cdxninteractive

Characteristics of the Best Restaurants

codes

Cooking Tips

CPM

CPM AD Networks

cpm adnetworks

cpm ads

cpm andnetworks

cpm based ads

cpm networks

cpm-adnetwork

cpm-adnetworks

CPM-Ads

Create a Membership Website

Create your own urls

Create-your-own-urls-referel-links-to boost-free-visitors-to-your-website

Credit Card Interest

Credit Card Rewards Programme

Crokery Shelf Designs

Dark PTP

Data courses

develop Telepathy

Did You Get Those Rankings?

Diet For Cancer Patients

Difficult Situations for Child Protection

Digital Marketing

Do Internet Marketing Delivers You Money

Documents Needed for Pan Card

dollars

Domain Business

double the traffic

Easyhits4u

emergency

Emergency Relief Network

Emily Wickersham

emily-wickersham-joins-ncis-as-series-regular

Energy Efficient Lighting

Energy Management

Energy Saving Tips at Home

English Grammar

ERN

Establishing strong relationships

euros

Exercise On Self Discovery

extra visits

Fair skin

Finance

Financial Planning

Fish Oil

Fish Oil Experiment

fix Spooler Subsystem error with your computer

Food and Heart Issues

foodripes

free

free ads

free advertising

free codes

free funds

free grants

free hits

free interest

free loans

free money

free organic visits

free payout

free samples

Free samples in India of products

Free Traffic

free us tarffic

free web traffic

free website traffic

freeads

generate

get ads placed

Get Current Time with World Time Server

get free grants

Get free samples in India of products online

get free traffic

get paid

Global Partnerships

Gold Backed Worldwide Currency

Good Morning

Google

Google Grants

Google-alerts-and-warn-searchers- users-of-using-search-words-and-13

Google+

Grants

Grimness of laughter

Healthy Eating Plan

Heaven letter

hits

Hollywood

Homeopathy

How CFL Saves Energy

How Disaster Makes people helpless

How Energy Can be saved in Kitchen

How Hyundai Automakers Test Their Cars

How to add photo to a pdf file

How to build a career in International Relations

How to get Pan from Us

How To Get US Traffic

How to Improve Your Memory

How to make money with QR Codes

How to spot an Email Hoax

How to Stop Installation Wizard from installing Windows Genuine Advantage Notification

HR

Human Resource is a social Science

ICT in Conflict & Disaster Response

Image Cherry

Impact of IT sector in Japan

Importance of Food Safety

Improve Memory

Improving Memory

Increase Organic (Free) Traffic

India

Indian Salary Calculation

Instant Approval CPM Sites

International Dev and Related Fields

Issues in Japan

Juiceadv

Key Resources for Funding Work in Peace building

Kindle Reader

Kitchen Designs

Know Date and Time

landing pages

Learn Telepathy Exercise

link back

links

Livelihood Programs during Tsunami by World YmCA

Loosing Weight

low

Low Calories Diet

low payout

Low Payout CPM Publisher

Made Red Wine Recipe

Make a Talk or a Speech

Make Red Wine

Make your Dreams Comes True

Making A Great Choice

Making Money With Niche Wesites

Management

Marketing

MBA

Media

Media.net

Membership Website

Memory Improvement Techniques

Memory Improvement Techniques 2

Mind Over Matter

Miss/Mr.Golden Globe: Presenting Hollywood's Next Generation

Mobile ad network

mobile ads

Mobile ads and networks you can use for us traffic uk traffic and other top nations

mobile advertising

mobile advertising network

money

Money Du

Motivational Exercise

Networks

New MBA Programmes

ngo

Niche Websites

NLM

NLM-Media

non profits

Note some points while making a speech or Presentation

Obstacles For Engineers Bound For Japan

Ojooo

Ojooo Adserver

page tools

Paid in euros

paid in us dollar

Paypal Mobile Publishers

per click

Performance-based campaigns CPM

Plant A Tree

pop ads

Pop Under Code

Pop Under Network

pop up ads

pop-up

popad network

PopAdvert

popup

popup ads

Post Tsunami Efforts in kerala

Power Of Brain

Powerful Revolvers

project

ProPtp

PTC

PTP

ptp ads

PTR

Publishing Tips and Tricks

Raksha Bandhan

Ranking

rapid action

Rapidhits

relief

Resources for Free Editing of Photos and Images

results

Role of personal value in our life

Rules of Management

Sales

Sample Aptis 121

Sample Grammer Aptis 2

Sample Grammer Aptis 3

Sample Grammer Aptis 4

Sample Grammer Aptis 5

Sample Grammer Question Aptis 1

Sample Speaking Aptis

Sample Vocabulary Aptis

Sample Vocabulary Aptis 1

Sample Vocabulary Aptis 2

seo tricks

Sexual body signals

Sexual Harassment at Work Space

sign up

signing

Social Dynamics

Speak up while making a presentation

Speaking Practice Exam

Speaking Practice Exam one

Steps needed to build up a Business

Stomach surgery

Successful Relationships

tags

Targeted Traffic for your website

Telepathy Exercise using Playing Cards

THE HAIR PREEN

The World of PIZZA

Things i found in a short Presentation

Traffic

traffic exchange

traffic-exchange

TrafficG

Training Law Enforcement on Child Trafficking

Tsunami Relief support by SDS-TFINS

Twenty Five Fair Tips

Twin Telepathy

Two dollar

Two dollar payout

unique visitors

United Nations Special Rapporteur

university of texas at austin United States

Unsolicited Phone Calls

Upload and Sell

URL

urladnetworks

urlads

urlnetwork

usa ads

use a custom domain name for your blog

Variable rate credit card

Very Important

Vinatge Ads

Vinegar Weight Loss1

Vinegar Weight Loss2

Vinegar Weight Loss3

Vitamin D

Vocabulary 1 Aptis Sample

Vocational Training for Tsunami affected people

Waiting for the Rain"

webmaster

Webmaster Quest

website

Website Monetization

Weight Loss

Weight Loss For 10 Pounds

Weight Loss Tips

What is Financial Literacy

What is the naughtiest thing you have ever done as an adult?

What skills are required for Training and Development Specialists?

Wheels on Meals

Wildlife

Wine Dining Tips

yahoo

Yahoo Invite Ad Network